April 21, 2017

What’s More Efficient Than a Person on a Bike?

Nothing!

We all know that bikes are amazing, but “amazing” may even be an understatement. Bicycles’ inimitable intricacies transform cyclists into the single most efficient moving entities on the planet, triumphing over nimble animals and grandiose machines. Bicycles are so exquisite that Steve Jobs admired them ardently throughout his career, referring to computers as “the equivalent of a bicycle for our minds.” What makes bikes so uniquely distinct that Jobs, who revolutionized the very nature of human interaction, chose them as the best analogy for his vision? What sets cyclists apart from other beings and machines, and how can one prove such a bold level of efficiency?

Jobs had learned about the efficiency of cycling from the article Bicycling Technology by S.S. Wilson, a former engineering lecturer at Oxford University and fellow of St. Cross College. In this piece, Wilson emphasizes that the beauty of bicycles largely stems from their “sheer humanity,” as the bicycle’s mechanisms function perfectly when intertwined with the power of human muscles. This brief point is pivotal to the understanding of cyclists’ unparalleled efficiency.

Bicycles and humans harmonize so seamlessly that they create a symphony of two, allowing cyclists to surpass cars, trains, planes, and even human evolution. The act of walking, for instance, exerts excess energy through actions as simple as standing up and swinging one’s arms. Cycling conserves nearly all of this energy, since cyclists sit down and don’t need to move their upper bodies very much. This design leaves a larger amount of energy to be used for pedaling, and minimizes the amount of energy that is wasted on extraneous actions. Further maximizing the cyclist’s power, pedaling primarily utilizes the muscles in the thighs, which are among the strongest muscles in the human body. Such extensive consonance between man and machine is almost unimaginable, yet cyclists bring it to life every day.

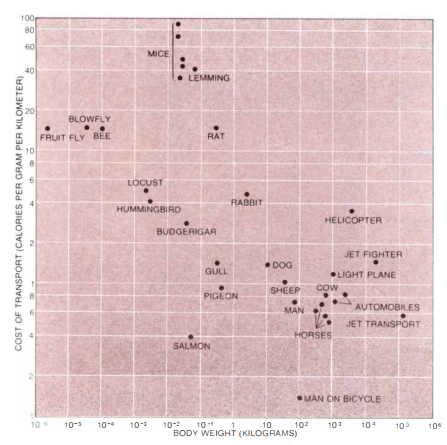

Wilson proves this logic with concrete data. Building on data originally compiled by Vance A. Tucker of Duke University, Wilson measures the efficiency of a cyclist in terms of the energy consumed in moving a certain distance as a function of body weight, using the unit of calories per gram per kilometer. Of course, this study operates under the assumption of regular conditions — flat surfaces and no extraneous weather circumstances. The findings reveal, “The rate of energy consumption for a bicyclist (about .15 calorie per gram per kilometer) is approximately a fifth of that for an unaided walking man (about .75 calorie per gram per kilometer).” Cyclists travel about three times as fast as pedestrians, and Wilson notes that they simultaneously use five times less energy. The raw data from Wilson’s study provides indisputable evidence of the bicycle’s pure illustriousness, therefore freeing the argument for bikes from any plausible deniability.

S.S. Wilson’s chart as seen in Scientific American, 1973

This study is from 1973, but it’s vital that we periodically remind ourselves about this information, as it continues to highlight the overwhelming importance of bicycles. Bikes are the perfect transducers for human locomotive energy, and among New York’s increasing bike lanes and thriving bike communities, there has never been a better time to be a cyclist. Next time you wrap your hands around your handlebars, remember that your activity outshines the cars and pedestrians beside you, the birds around you, and the planes above you.

Alison Rosenberg is a Communications Intern at Bike New York. She is an English and sociology major at Kenyon College.

![AdobeStock_65147919 [Converted]](https://www.bike.nyc/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/AdobeStock_65147919-Converted-640x640.jpg)